The islands of the Venetian lagoon have been populated for millennia. The lagoon is a productive fish habitat and a beneficial environment for a large range of shellfish. The salt marshes provide nesting and over-wintering sites for over 60 species of aquatic birds, the largest population of water birds in Italy. Long before the Romans, fishermen and fowlers inhabited the islands.

Torcello is often portrayed in literature as a place of refuge, enlightenment or respite before the confusion, the harshness of reality descends on a character. For example Du Maurier’s characters in “Don’t Look Now” experience a brief respite from confusion and sadness while on the island. Ignoring the messages offered to him on Torcello sets the protagonist on the path to certain death.

In “The Stones of Venice” Ruskin’s pose as the superior, expert judge of all things Venetian can be irritating beyond belief. His many errors of fact and interpretation - for example he was blind to the presence of Burano and Mazzorbo a few hundred metres across the water from Torcello - have engendered fury in his critics. But there is, beneath the pose and the elaborate phraseology, a humanitarian instinct and a vision that makes reading his book worthwhile. His lyrical description of Torcello begins:

In “The Stones of Venice” Ruskin’s pose as the superior, expert judge of all things Venetian can be irritating beyond belief. His many errors of fact and interpretation - for example he was blind to the presence of Burano and Mazzorbo a few hundred metres across the water from Torcello - have engendered fury in his critics. But there is, beneath the pose and the elaborate phraseology, a humanitarian instinct and a vision that makes reading his book worthwhile. His lyrical description of Torcello begins: Seven miles to the north of Venice, the banks of sand, ..., attain by degrees a higher level, and knit themselves at last into fields of salt morass, raised here and there into shapeless mounds, and intercepted by narrow creeks of sea. One of the feeblest of these inlets,... stays itself ... beside a plot of greener grass covered with ground ivy and violets. On this mound is built a rude brick campanile, of the commonest Lombardic type,

This “rude brick campanile” is the bell tower of the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta.

This “rude brick campanile” is the bell tower of the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta.Long before the bell tower was built, long before Christianity came to Italy people inhabited the marsh islands.

By 100 A.D. grand Roman holiday villas were situated on Torcello. Torcello first rose to prominence as a refuge for the people of the mainland escaping the invasion of the Huns in 452 A.D. By 466 the first steps toward a united community in the lagoon islands had been set up.

Torcello was abandoned within a few generations of the signing of this agreement because an earthquake in Northern Italy generated a tidal wave that flooded Torcello and sent the survivors fleeing back to the mainland or to other island communities.

When the Lombards invaded Northern Italy in 568 A.D. refugees fled once again to Torcello. This time they stayed.  By the time the building of the cathedral began in 639 A.D. a monastery and the lagoon’s first nunnery (both dedicated to St John) had been established.

By the time the building of the cathedral began in 639 A.D. a monastery and the lagoon’s first nunnery (both dedicated to St John) had been established. Over the following centuries with their rise in fortunes the inhabitants of Torcello extended the cathedral until by the end of the first millennium A.D. it looked very much as it does today.

The bell tower was built at this time and the building of Santa Fosca church, a martyrium to house the saint’s remains, had begun.

Torcello became a hub of industry, an important port, a link between Italy and the Adriatic, and interestingly, a glass-making centre.

It was on Torcello that Venetian-style glassmaking developed from the earlier Roman techniques which were first employed on the island. These skills were then transferred to Venice and from Venice to Murano. Murano later became a centre of glassmaking and, for a time, a world leader in the development of a range of glassmaking styles and techniques.

It was on Torcello that Venetian-style glassmaking developed from the earlier Roman techniques which were first employed on the island. These skills were then transferred to Venice and from Venice to Murano. Murano later became a centre of glassmaking and, for a time, a world leader in the development of a range of glassmaking styles and techniques.In the twelfth and thirteenth century the exquisite mosaics for which the basilica of Santa Maria Assunta is world famous were installed. Although Torcello was producing glass at that time research shows that the original glass used for the mosaics was produced in the Levant and then reworked at Torcello.

In the 1300s Torcello was abandoned because of silting in the lagoon and outbreaks of malaria. As Venice increased in power and prosperity Torcello declined and its buildings were demolished, the materials moved to the rising star of the lagoon, for building materials were scarce and expensive in that watery environment.

The low lying open space of Torcello gives it a tranquil atmosphere that has drawn many famous writers.

The low lying open space of Torcello gives it a tranquil atmosphere that has drawn many famous writers.Hemingway was one. He wrote “Across the River and Into the Trees” during a stay on this island in 1949.

But it is a lesser known writer whose comments about Torcello and its inhabitants who most appeals to me. W. D. Howells visited Torcello during his period as American Consul in the 1860s. He wrote about this experience in “Venetian Life”. His quote is in blue print.

His observations about his visit to Torcello contrast with those disappointed comments about the island by Henry James, and the remarks about Burano by the anonymous author of the New York Times article of 1880.

Torcello has a Devil’s Bridge over a small canal. It is probably so called because it has no hand rails. A visitor after indulging too well at Torcello's Locanda Cipriani, a restaurant almost as famous, and expensive, as Florian’s in St Marks Square, could well topple into the canal from the bridge.

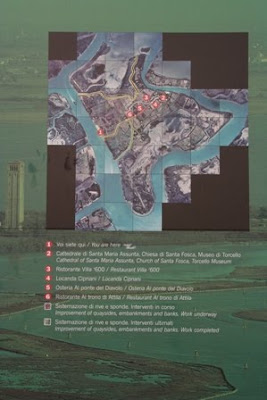

Today Torcello is as Ruskin, James and so many others described it: an island barely above sea level with a small group of buildings which includes the Basilica, the church and the belltower at one end, with a small population of guards, guides and souvenir sellers who welcome the visitor. It is easy to imagine staying there for an extended period, observing the rise and fall of the tide, the cycle of the seasons beneath those open skies.

Observer

9 June 2010

email: longline8@gmail.com

Ref:

W.D. Howell, "Venetian Life", 1867.

F.C. Hodgson, "The Early History of Venice"

John Ruskin, "The Stones of Venice", 1879

Henry James, "Italian Hours" 1909

Ernest Hemingway, "Across the River and Into the Trees" Jonathan Cape, 1950

Daphne du Maurier, "Don't Look Now and Other Stories", Penguin, 1973David Hewson, "The Cemetery of Secrets" Pan Macmillan 2001

Observer

9 June 2010

email: longline8@gmail.com

Ref:

W.D. Howell, "Venetian Life", 1867.

F.C. Hodgson, "The Early History of Venice"

John Ruskin, "The Stones of Venice", 1879

Henry James, "Italian Hours" 1909

Ernest Hemingway, "Across the River and Into the Trees" Jonathan Cape, 1950

Daphne du Maurier, "Don't Look Now and Other Stories", Penguin, 1973David Hewson, "The Cemetery of Secrets" Pan Macmillan 2001